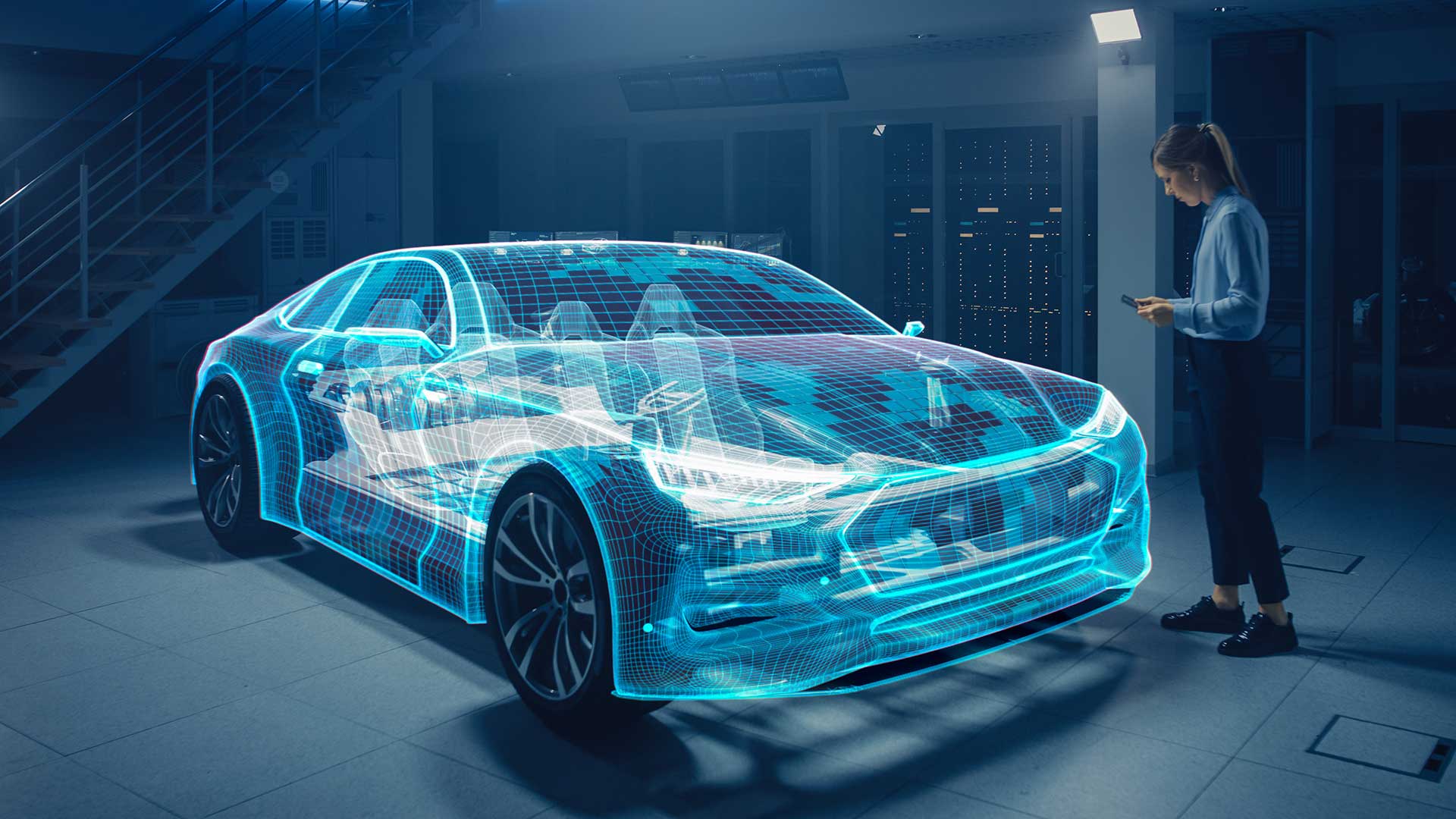

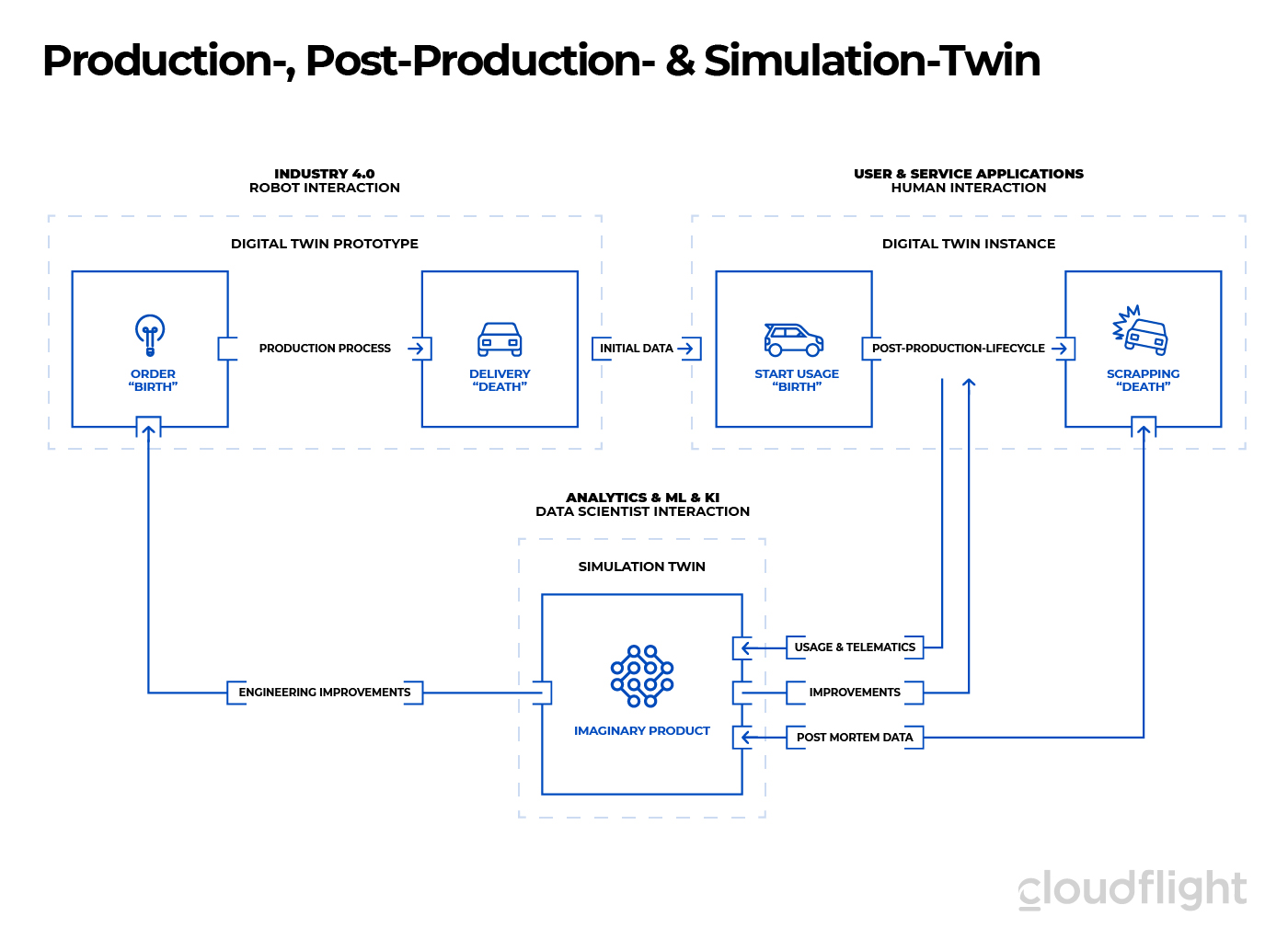

The great potential of the automotive industry is a digital ecosystem for future consumer and B2B vehicles alike. Experts in the vehicle industry agree that this can no longer be mapped with proprietary point-to-point communication between software applications and vehicles. In the recently published article “The architecture for an entire vehicle twin life”, Cloudflight presented a technical solution approach in cooperation with Linde Material Handling as an innovative representative of B2B vehicle manufacturers. A digital “post production twin” abstracts the communication to the vehicle and always represents the current status of a vehicle network with high-performance interfaces in the cloud instead of communicating directly and individually with the vehicle. This second article now specifically addresses CXOs and industry lobbyists to discuss and propose a community’s strategic approaches to implementing this concept. We are now specifically pursuing the question of whether and how Linde Material Handling and other companies in the industry can create an open ecosystem.

While a great deal has been accomplished in Industry 4.0 with respect to the automation and digitisation of production, standards are largely lacking for the post production life cycle. Although collaboration between vehicles in a fleet as well as any vehicles in public transport (V2X) would be important here in particular, there are only proprietary solutions on the market. Many use cases such as the digitisation of service processes, the sale of digital add-ons, or modern fleet management do not succeed because each application speaks individually to each vehicle of each manufacturer. Some of you may remember enterprise software landscapes before the invention of modern middleware. Today, modern middleware such as a service bus, event management, adapter framework, or API management is indispensable for enterprise software in the data centre as well as in the cloud. These software concepts allow us to combine ERP, CRM, eCommerce, or HR systems from different manufacturers. This is precisely the task that a digital twin for the vehicle industry can fulfil over the entire life cycle of the vehicles – if several manufacturers were to agree on a concept.

One of the pioneers in the vehicle industry with regard to the digital twin is the company Linde Material Handling, which is part of the KION Group and is best known for its forklifts. Linde MH has been supplying forklifts with a post production twin since the beginning of 2020. This twin is modelled and implemented so generically that it can not only be easily adapted for other parts of the company and vehicles in the KION Group but also even serve as a blueprint for the vehicle industry.

Cloudflight has already published several papers on the topic of IoT platform strategy . Strategically, vehicle manufacturers such as the KION Group have various options for dealing with digital twins and domain-specific IoT platforms:

- In-house development of the twin/IoT platform and the applications: Companies differentiate themselves on the market through their products and software applications. The underlying platforms are often not even transparent for clients. Manufacturers should therefore definitely write the software applications that are visible to their customers and service partners themselves. If the necessary platforms are not offered by software vendors and there are no co-innovation or community models in place, the domain-specific parts of the platform must also be developed in house. This path taken today means long-term investments in basic technology and is critical for smaller vehicle manufacturers.

- Wait for the digital twins from software vendors such as Amazon, Bosch, IBM, PTC, and SAP that can generically map EE architectures for post production twins. As soon as there are solutions for the vehicle industry that are really at the level already achieved today, it will be possible to migrate the platform to one of these manufacturers and focus on their customization and the development of the applications visible to customers. Although this may still take a few years, it will generate significant licensing costs or a provider lock-in. Today, data models do not relate enough to the vehicle industry, or the runtime performance for millions of twin assets can hardly be represented cost-effectively over decades.

- Form a spin-off in order to market the twin data architecture and its implementation or even its cloud-native operation beyond the group of companies. This is a pure software business in which a vehicle manufacturer is in unfamiliar territory. Partnerships or co-investment with a software provider may be a solution. A negative lock-in can be avoided through a permanent participation of one’s own company and other vehicle manufacturers in the spin-off.

- Form a community approach with peers among manufacturers and service companies that focuses on the further development of the twin core. Here, the platform with data models and APIs is defined by a non-profit community, while independent IT service providers offer commercial implementations of the emerging standards.

The right path ultimately depends on the level of development of the industry. Two years ago, not even a single vehicle manufacturer had been able to map the entire electric-electronic vehicle network across the entire vehicle age. Even in the aerospace sector, only individual parts (e.g. the turbines) were represented by complete twins. Pioneers such as Linde MH therefore had to develop applications and the digital twin core themselves. The lead over manufacturers that could adapt cross-industry software is still immense. This makes option 2 combined with significant licensing costs still less attractive today. Let’s take a closer look at the possibilities of a spin-off or community:

The vehicle industry had a similar challenge 25 years ago, when the complexity of the EE architecture was no longer manageable – even with many ECUs from different manufacturers. Mixing control units from Bosch, Brose, and Continental in one vehicle was highly attractive from a functional and cost perspective but impossible from a practical perspective. This led to the joint definition of the AUTOSAR architecture by car manufacturers and the supplier industry in 2003. To this day, it forms the basis for the interoperability of control units from different manufacturers WITHIN a vehicle. It is now time for the automotive industry – not only the manufacturers but also the service and maintenance providers – to launch a data architecture for vehicle twins that connects vehicles EXTERNALLY to the cloud across manufacturers.

Cloudflight had already examined the digital twin of Tesla in its own expert view. While there is much to be learned here about the distribution of data between a technical twin and a remote twin, the approach is by no means open or suitable for a community approach. In contract, it is natural to discuss the Linde MH approach as a blueprint for a community approach. Why does Cloudflight think such a community could work?

The same automotive industry that would need to come together here has already formed similar industrial communities around commercial manufacturers for Industry 4.0 manufacturing. A good example is the Adamos alliance of the IoT software manufacturer Software AG or the Mindsphere ecosystem of Siemens. IoT before and after production is similar – and yet so different. On one hand, the Industry 4.0 wave has done a great job in terms of technology and the organisation of the industry. On the other hand, it has mostly completely neglected the product in the post-production life cycle. It would thus be a good time to build a community around post production twins for the entire vehicle industry. Strategic steps to this end could include the following:

- Learning from Industry 4.0 and AUTOSAR: Automation in manufacturing has a long tradition. Data architectures develop interoperability between different systems along the production line. Here there is also the “Asset Administration Shell”, which can theoretically also map a digital twin of finished products. In reality, however, it is more the means of production than the products that are depicted here. There is therefore also a mapping to the automation architecture OPC Unified Architecture (OPC-UA), which is moderated by the OPC Foundation. AutomationML can also be mapped on this Industry 4.0 management shell. Larger service providers or alliances of industry and software manufacturers such as Adamos offer frameworks and predefined data structures for individual sectors. The Industry 4.0 approaches are collaborative across several participants in a supply chain. Unfortunately, these can be elaborated only for the automation itself and not for a moving vehicle network with telematics data. On the other hand, the AUTOSAR standard covers detailed communication between controllers in a vehicle. It was never intended for communication out of the vehicle or even for collaborative communication in the cloud.

- Combine a non-profit foundation and a commercial consortium:

Data standards can be particularly well established when they are formed without commercial conflicts in a non-profit consortium. This is what the European Data Strategy did with the Industrial Data Spaces Association, which was formed around the Fraunhofer Gesellschaft. This is now also accompanied by commercial software and infrastructure providers with the Gaia-X approach. Companies can set up communication that is compliant with industrial data spaces or switch between commercial providers. In the US, the Digital Twin Consortium has already been formed. It is led by the OMG, which is also responsible for the Industrial Internet Consortium. In Germany, there is a parallel Industrial Digital Twin Association, which was founded by the VDMA and ZVEI together with Bitkom. Unfortunately, associations mainly pursue the industrial production twin in the Industry 4.0 context as the Industrial Digital Twin Association confirmed at Cloudflight’s request. In principle, the definition of a post production twin or the cooperation with an association that focuses on this is also conceivable.

- Build a commercial ecosystem: Especially smaller vehicle manufacturers or independent service companies of B2B vehicles are usually too small to invest in IoT platforms themselves. It would be ideal if there were a commercial spin-off from leading companies in terms of content (e.g. the KION Group) but without exclusivity. While there should be exactly one standard consortium, it is the other way around for commercial providers. Healthy competition from commercial providers offering vehicle twins as a SaaS solution or custom modelling and software implementations is innovative and brings the API data standard into the market.

- Initiate co-innovation with telecommunication companies and hyperscalers: Vehicle-to-twin communication has certain strategic parallels with the vehicle-to-vehicle communication and 5G challenge of the automotive industry. Professional cellular connectivity is also essential for the digital twin of vehicles in the field. It can thus make sense to place parts of the twin infrastructure in the 5G multi-access edge . In this area, the hyperscalers are currently cooperating intensively with the telecommunication companies.

In summary, a spin-off from Linde MH could make the concept of a digital twin accessible to the entire vehicle industry. However, it will take on real market momentum only if a non-profit community is formed in parallel, so that the existing data and API architecture can be further developed into a recognised standard.

Which path Linde Material Handling and the KION Group will ultimately take has not yet been disclosed to the public. It could also depend on the response in the industry to these two articles.

On the way to a standardised vehicle twin, strategists and lobbyists should never forget: The vision has many examples! The digital twin could be as revolutionary for the vehicle industry as the standardisation of the USB plug was 25 years ago with a uniform protocol for various devices in the computer industry. It is now up to the manufacturers and the service companies to bring such a standard for digital multi-access interaction with vehicles to life.