Public Clouds and the “Public Sector” are almost namesakes, but the two domains couldn’t be more different in Europe. This widely confusing situation is mostly mutual: while the cloud providers have ignored the needs of the public administration for years, many decision-makers and CIOs government agencies have had predominantly false notions about what a cloud provider is and what makes it different from a data center. On top of that there is the authorities’ traditionally defensive policy towards the citizens’ data. Despite the industry’s 10-year track record of facing the public cloud with a positive attitude, the public sector is going the opposite way. This trend is also in contrast with the fact that the cloud providers gave advocates the task of finding out how and which upsides of the public cloud are effective for companies. Here, privacy advocates and lawyers consider their task mostly telling CIOs and administrative managers what they CANNOT use. In most cases, this is what led to advantages of the public cloud – like agile application development or cloud native orchestration of PaaS services – never making it into the public sector.

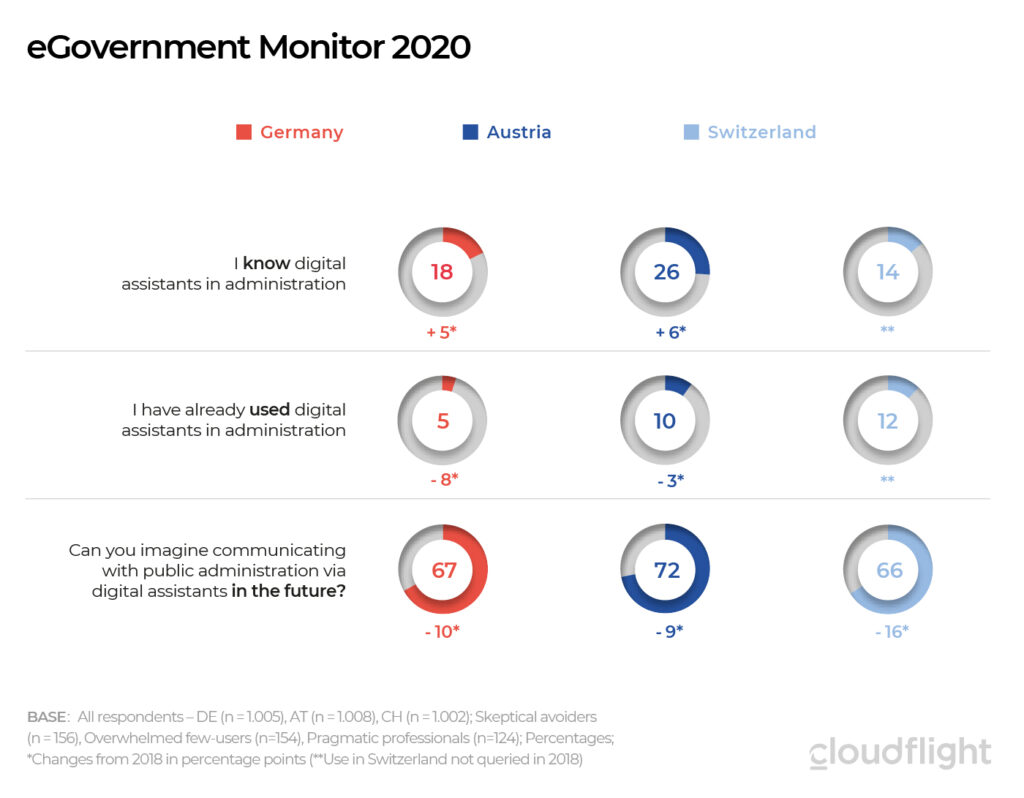

Finally, the pandemic also steepened the citizen’s expectations for the State’s digitalization, regardless of whether we’re talking about a digitalization of the education system or of things as simple as the issuing of vaccination appointments. The number of citizens that consider a “total digital failure” was alarmingly high already before the pandemic: in particular, an outstanding 90% of tomorrow’s voters in an age range from 18 to 29 have already used the State’s digital services but, according to a survey from Accenture, only 11% were satisfied with them. The current 2020 eGovernment monitor still shows that, even after the Corona lockdown, there is a low 18% (26%) awareness around Germany’s (Austria’s) digital administrative processes, and a devastatingly low user acceptance — amounting to 5% in Germany and 10% in Austria.

Cloud is not just cloud. The three categories Infrastructure-as-a-Service (IaaS), Platform-as-a-Service (PaaS) and Software-as-a-Service (SaaS) are already “traditionally” established. The figure shows the distribution of work between the cloud provider and the customer on the three levels. While all three types are merrily mixed in many commercial enterprises, the public sector requires a more precise distinction:

Where is the data and who can access it?

If you look at data protection positively – which means under the premise of how something is possible and not under the premise of why something should be avoided — two basic subject areas quickly emerge.

- Data-Residency – Where is the data stored? After the homogenization of the European privacy protection with the GDPR, prominent lawyers in the field stated to Cloudflight, the EU country in which the data is stored doesn’t matter anymore. So, whether authorities in Austria localize their data in Austria itself, Germany or Ireland is irrelevant, because EU data protection has replaced national regulations.

- Administrative Jurisdiction – In which jurisdiction does the administration take place? The fact that the data is stored in the EU doesn’t mean that only employees from the EU have access to it, or that they treat it in compliance within the EU jurisdiction. Especially with international providers, systems are administered around the clock from different countries. Whether and how data in the EU can be accessed from outside is described by laws, landmark judgments and sections in the contracts. The EU-US Privacy Shield Agreement (https://www.datenschutz.org/privacy-shield) should have simplified this legal situation, but was declared ineffective by the European Court of Justice (ECJ) on July 16, 2020. The large providers have therefore reverted to the older so-called EU standard contract clauses. With this construct, a provider undertakes that all employees and subcontractors who have potential access to data or meta-data, will adhere to EU data protection – regardless of the country or jurisdiction they are in.

The question about Data Residency was de facto solved already a few years ago by all three American hyperscalers – the fast-growing providers Amazon Web Services (AWS), Google Cloud Platform (GPC) and Microsoft Azure. All three providers offer data centers in the EU, and they even offer all three categories (IaaS, PaaS, SaaS) from the EU. As for Administrative Jurisdiction, the three big clouds provide EU standard contract clauses. But can the public administration or the authorities trust such a vague legal construct? This is in fact the main critique coming from privacy advocates. The answer lies once again in the difference between IaaS, PaaS, and SaaS.

Green light for the IaaS service in the public sector – even for confidential data

We see a quite positive situation for IaaS services, i.e. virtual computing power and simple storage services.

- The IaaS Providers have ideally no access at all to data. In traditional IT, a server operator always has access to the data. In modern cloud infrastructures things are different! AWS and GCP in particular encapsulate the actual client data and entire virtual machines in a modern hardware encryption (see AWS Nitro Enclaves or GCP Confidential Computing). This way the cloud-provider can also certify that they have no possibility of reading the data at all, regardless of the access origin.

- Regulators bear the complete responsibility and expertise. In order to understand this high level of security and take advantage of the many tools the providers offer, the authorities’ IT personnel must either know their way with the topic very well. Alternatively, they should bring in the help of a European cloud native operations company like Cloudflight. The public cloud provider will not provide these further services – as this would require at least some metadata access.

Basically, there is no need to trust the EU standard contract clauses in the IaaS case, because the public cloud provider makes the virtual infrastructure available without a single employee having access to real data – if the private key and encryption tools offered are used correctly. Hence the possible access country becomes irrelevant.

Particularly in Germany and in France, the call for the so-called data sovereignty is strong and will be pushed further at a national level through the Gaia-X initiative. With modern IaaS infrastructure and the aforementioned tools, a public agency would be able to achieve this intrinsic control over all the data already at present, even if the data is physically stored in a data center belonging to an American provider. The administrative jurisdiction – and so the group of people with real access to the data – will be determined by the public agency and not by the cloud provider. The effort to understand this, in reality, isn’t much more significant as that to understand the new Gaia-X methods that are still not operationally available as of today. (See also our recent publication “Why GAIA-X hasn’t been successful yet”).

The strive to establish IaaS services in the public sector, however, is worth it when it comes to modern applications that, for example, have different loads throughout the day, like all self-service “eGovernment” apps. As soon as the number of users decreases, the generated architecture melts away and is created again in a matter of minutes once the capacity is required. This can cut costs significantly and, at the same time, generate better user satisfaction. An example could be the Deutsche Bank, that generates this way its own Google GCP for BAFIN-regulated financial data. However, this still doesn’t provide more agility to the creation of new applications.

PaaS services bring speed of innovation for certain data

The PaaS services are quite different from pure infrastructure as shown in the figure, from here the cloud provider takes over the complete technical administration. Examples are the database-as-a-service or the dynamic function-computing. Many modern hyperscaler PaaS services are encrypted so that the cloud operator can’t see the content, even if they would violate the contracts. However, the metadata must be processed in order to be able to operate the service in complete security. For instance, a cloud provider can defend a DDOS attack against its PaaS service, only if they process the access’ IP numbers and block criminal bot-nets. Hyperscaler PaaS services in public administration or in education are, in general terms, a good option if:

- The data in the PaaS service is encrypted. Unfortunately, this brings also along significant limitations. It is understandable that a database with encrypted data can’t be indexed or browsed efficiently: in this case, the solution is a modern service design that allows to process personal data fragments in a IaaS service, while bigger data volumes are on PaaS with secret keys, that can be read in services. Anonymization and pseudonymization are the key terms – only an application on the IaaS service knows the relationship between these keys and the actual personal identities.

- The EU model contract clauses are enough for processing of the meta-data. This is actually more possible than one would think at first. Basically, every tourist that turns on their smartphone in any EU state outside the home state, is already sharing metadata with a roaming mobile cellular network at this level. The processing of this metadata via third parties is already widely accepted by the citizens.

In order to be able to use PaaS services, the CIO must bring together the privacy advocate and the database’s designer. If it is possible to separate the smaller part of the very sensitive data from the larger part of the encryptable or less sensitive (meta) data, the PaaS services can be used. Background data classification, sensitive data according to GDPR

This is particularly important for the distinction between metadata and user-generated contents on one hand, and the clear distinction between personal, sensitive and anonymized data on the other. Metadata are descriptive data such as network information (IP addresses, time, transmission protocols, etc.), while user-generated contents represent the content created by the user, such as texts or messages.

According to the EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), personal and sensitive data are to be protected. Personal data is all data that either identify someone (name, address, date of birth) or make them identifiable with relatively little effort (e.g. license plate number, IBAN, etc.). Sensitive data or special categories of personal data are personal data from which ethnic origin, political opinions, religious or ideological convictions or trade union membership emerge, as well as the processing of genetic or biometric data for the unambiguous identification of a natural person, health data or data regarding the sex life or the sexual orientation of a natural person. In reality, many CIOs, IT managers and data protection advocates will be surprised at how large the amount of data is that is transiently volatile, non-personal or encryptable. The use of PaaS services for this actually brings enormous agility when creating new eGovernment applications. In addition, the orchestration of cloud-native PaaS services requires far less detailed technical knowledge than the diligent use of IaaS services. This ultimately brings the speed of innovation in software development from the free economy to the public sector.

SaaS services remain the major headache of public administration and education

SaaS services are complete applications such as Microsoft’s Office 365 or the competing Google Workspace offer. SaaS also includes complete business applications such as Customer Relationship Management (CRM) by Salesforce.com, to name just one example. As the figure already suggests, the user has practically no responsibilities or duties here, apart from a few configuration settings. The overall infrastructure, underlying platform and software application are completely managed by the SaaS provider.

In order for these SaaS applications to function properly, all data must be in the cloud. Even if all reputable American providers have now been able to comply with the request of data storage in the EU, the SaaS application can only be used today if you trust the EU model contract clauses. To clarify the high level we are already at, here’s an overview of the facts:

- Office 365 and Google Workspace adhere very rigorously to European data protection in accordance with the GDPR.

Google GDPR:https://cloud.google.com/security/gdpr?hl=de

Microsoft GDPR:https://www.microsoft.com/de-de/trust-center/privacy/gdpr-overview

- Google and Microsoft are certified to the highest possible level. This has now reached a level that can hardly be reached by local cloud providers.(https://cloud.google.com/security/compliance)

- Microsoft and Google provide statistical and case-by-case transparency and have fixed processes for inquiries from law enforcement and government agencies. These include requests from the NSA, CIA and the FBI as well as from the Interpol. According to the EU standard contract clauses, inquiries from secret services are only allowed from the relevant jurisdiction. For example, in order to comply with the EU standard contract clauses, Google generally rejects requests for workspace data that belongs to EU customers from all authorities except the Interpol. Possible accesses by Interpol are made transparent to the customer in individual cases and you have the opportunity to file a complaint BEFORE access. Nevertheless, individual court procedures might affecting EU data from the US. Both SaaS providers publish statistics and these individual cases as well as a precise process description on a regular basis (see https://transparencyreport.google.com/ and https://privacy.microsoft.com/de-de/privacy-report ).

- Microsoft and especially Google separate their workspace products clearly from other business models – especially from advertising. Google is known for its advertising business, which is almost ten times bigger than the commercial cloud business for companies and for the public sector. Thus, Google separates its cloud business from its advertising business. For 15 years there has not been a single documented case, or case known to Cloudflight, in which data from Gmail or Google Docs (now part of Google Workspace) was used to profile people or even for advertising purposes or leaked to other users. Nor do you suddenly get advertising for a SurfacePro from Microsoft, even if, for example, you ask your IT department for a new PC via Office 365 Mail. The contracts here exclude very explicitly the companies from viewing the data and, of course, from passing it on to third parties.

This level of transparency is at a so much of a high level that hardly any municipal or state data center in Germany can match it. Some state data centers in Germany (e.g. Belwue in Baden-Württemberg) don’t have neither basic certifications (ISO 27001) nor such a transparency obligation.

An exchange of data with agencies in the same country as the LKA is allowed in the terms of use and does not even have to be communicated to the concerned citizen. When it comes to preventative data storage by the police – which was legal in Bavaria for a few months – progressive data protectionists see the residual risk of improper use. This is perceived as significantly lower with American hyperscalers rather than with state data centers in Germany.

Most commercial enterprises now trust the EU model contracts and recommend this also for public applications such as the education sector.

To be very clear, not trusting the EU model contracts means to accuse the cloud provider of negligent or even willful breach of contract. A negligent violation would take place if, for example, a Google employee outside the EU – e.g. in the USA or Switzerland – steals and sells data from the EU. Due to the contractual situation, he would have to adhere to EU laws. Due to the contractual situation, however, European criminal justice has only limited options.

SaaS Wishlist – What cloud providers should do for public administration

You can see that the above mentioned examples are already very constructed cases and have occurred extremely rarely or never before. Nonetheless, the theoretical possibility of violating of all contracts is enough for data advocates not to recommend the SaaS models (anymore) to public industries such as health care, police detection data and even the education field. The missing step is very clear, albeit technologically challenging:

- Administrative EU-Fence — A virtual fence for administrative access. This refers to the technical restriction of access by administrative persons to systems that contain EU data.

That sounds easy to do when you think about the hosting of traditional applications. Cloud native applications such as Google Workspace in particular did not emerge from traditional applications (such as Microsoft’s OneDrive from the Sharepoint server) and cannot simply be administratively divided into regions. For example, one team around the globe looks after the file system, another looks after identity management and a third looks after certain applications in all data centers. Keeping all teams available for 24/7 operation in a region is not only significantly more effort, but would also call into question the entire operating concept of global cloud providers. Normally, all locations are supplied with the same software with only a few minutes or hours of delay. Every single one of the one billion Google Workspace users around the world uses exactly the same software version.

The public sector should keep talking with the hyperscalers

Cloudflight has been following the cloud market for more than 15 years. Ultimately, the three most successful American companies in particular, AWS, Google and Microsoft, are extremely customer-driven. That’s why they’re so successful. This may not seem so to many in Europe, because in this area the use and thus the influence on the market leaders is still comparably small. In order to communicate a need to these companies, a customer or prospect has to establish in dialogue to begin with. Very little separates us from the secure use of PaaS and SaaS solutions from the cloud. Services such as an “Administrative EU Fence” would most likely be on the table if entire countries decided to negotiate with Microsoft or Google, or if they made clear legal requirements.

Older readers will still remember that 15+ years ago Microsoft tried to inseparably connect its Internet Explorer with the Windows operating system by using massive marketing power. Public administrations in particular were looking for alternatives with Linux desktops with good reason – similar to what Germany does with Gaia-X in the cloud today. At the same time, however, the constructive discussion with Microsoft didn’t stop. Clear support from the European Court of Justice ultimately led to the fact that today all leading browsers (Google Chrome and Microsoft Edge) are based on the open source Chromium, which is openly and transparently – Linux desktops included. At that time, the entire EU stated the clear need to avoid monopoly. We now need the same joint yet constructive approach to privacy in PaaS and SaaS services. Only then will many of them still be successful in ten years’ time and run effectively on both hyperscalers and local Gaia-X providers – like browsers on various end devices today.

The EU cloud code of conduct targets the right direction (https://eucoc.cloud/). While the major cloud providers adhere to the agreement, each data protection authority across the EU countries agree to it at different speed.